Customs, Traditions, and Culture

From the practices and conduct of a community, it becomes clear how that community is distinct from others, and what its social status is. Every community has certain unique features, and it is on the basis of these that it is identified as separate. To preserve these distinguishing practices within their community, the leaders and respected members always remain vigilant. Over time, these distinct practices become established as customs and traditions in society. These very traditions then gradually become an inseparable part of the community, and in fact, the daily conduct of its members. Thus, the ways once adopted and practiced by the forefathers of a community were passed down to the next generations, surviving till today, and gradually became firmly rooted as their culture.

In our country, many such cultures have come together. Yet, communities have managed to preserve their distinct identity and uniqueness. In recent times, however, the rigidity of certain binding customs has lessened. Science, education, and changing circumstances have been the driving factors behind this. Even so, the transmission of culture to the next generation continues and will continue in the future.

While human beings have adopted many good practices into their conduct to make life happy and prosperous, it is equally true that they have also fallen prey to harmful practices, blind beliefs, and superstitions, which have led to their own destruction as well as that of their community. Culture must enrich the human being, shape him as a complete person, and make his life purposeful and beneficial. Such is its true essence.

This is the wish of all humankind. In truth, good customs, traditions, and conventions are those which serve the welfare of society. Only the harmful and undesirable practices must be discarded.

The priceless treasure of good conduct and habits is passed on by each generation to the next. Thus, practices established since time immemorial continue into the future. In this process, some old customs gradually disappear with the passage of time, while some new ones make their way in. As values (saṃskāras), every community transmits these to its successors. This flow has continued ceaselessly since ancient times.

Just as many communities have preserved their unique characteristics, so too has the Periki community. While their customs resemble those of many other castes within the wider social group, they have retained their own distinct features. Since many rituals are performed by priests, and the same priest often serves several castes, it is natural that similarities exist among their ceremonies. The same is true in the case of the Perikis.

Among the Ṣoḍaśa Saṃskāras (sixteen life-cycle rituals) prescribed in Hindu tradition, the ancestors of the Perikis had adopted several into their conduct. Today, however, their practice has become almost negligible.

Considering all these customs, traditions, and conventions, it appears that these were systematic human efforts to destroy misfortunes and evil forces and to strengthen auspicious powers, thereby making human life easier and more prosperous. The Perikis are no exception to this.

In the following, a detailed discussion of some of their saṃskāras is given, covering the rituals from birth to death.

Garbhādhāna (Conception Ritual):

Among the sixteen saṃskāras, the first is Garbhādhāna. Its definition has been given by Śaunaka as follows:

“Niṣikto yat prayogeṇa garbhaḥ sandhāryate striyā,

Tad garbhālambanaṃ nāma karma proktaṃ manīṣibhiḥ.”

That is to say: By the performance of this rite, the woman retains the conception bestowed (by her husband). This rite is called Garbhālambana (conception ritual) by the sages.

This is what scholars call Garbhālambana (Garbhādhāna).

In the earliest stages of human life, conception or childbirth was regarded simply as a natural act. At the moment of desire for pleasure, man and woman came together, not with the intention of begetting children, but rather to satisfy the senses through union. Beyond this, the act held no ritual or cultural significance. The very idea that Garbhādhāna could be a saṃskāra belongs to a later stage, after humankind emerged from its primitive condition.

With the development of the home, the institution of household life, the aspiration for offspring, and the belief that divine grace was necessary for the blessing of children, the foundation of today’s Garbhādhāna Saṃskāra was laid.

In the pre-Sūtra period, this rite was extremely simple. The husband would approach his wife after her ṛtusnāna (menstrual bath). He would invite her for conception, pray to the deity for the implantation of the embryo in her womb, and then consummate the union. Beyond this, the rite had no further ritual embellishments.

In later times, however, many elaborate practices began to be added. Numerous injunctions and prohibitions grew around it. Rituals concerning whether the child would be a boy or girl received great emphasis, and attention increasingly shifted toward such ceremonial formalities.

In the present day, much of the unnecessary ritualistic side of the practice has gradually disappeared. Instead, among the Perikis in particular, Garbhādhāna came to be observed as a social custom. On the night of union, the husband and wife performed Gantā Pūjan and took the blessings of their family deity, Mallanna (Śiva). Later, the elder women of the household seated the couple together, filled the wife’s lap (oṭī bharṇe), decorated the bed, lit a lamp beside it, and placed a plate of sweets and a betel-nut casket nearby. On the following day, the couple was again seated together, a sacred thread (gantā antharun) was tied, and an ārati was performed for them. In Maharashtra, this custom is called Śiḷī Kurvaṇḍī (Bhāsaṅko, Vol. 2, pp.748–49).In modern times, however, this saṃskāra has completely disappeared.

Puṁsavana (Rite for Begetting a Son):

It appears that the desire to have a son has existed since ancient times. Even today, the wish for the birth of a son is strongly evident. It is for this reason that the ritualistic efforts undertaken to ensure the birth of a son seem to have originated in the Puṁsavana Saṃskāra.

It becomes clear that this rite is to be performed while the child is still in the womb, and therefore it is also called Garbhasaṃskāra. This ritual is carried out to impart masculinity (puṃsatva) to the fetus and to ensure its growth. In Saṃskāra Prakāśa, the definition of Puṁsavana is given as follows:

“Pumān prasūyate yena karmaṇā tat puṁsavanam īritam.”

That is, the act by which a male child is born is called Puṁsavana.

The birth of a son was considered especially important for the Kṣatriyas, since they always needed brave young warriors for battle. As the Perikis were originally Kṣatriyas, they too must have felt the need for valorous sons, and therefore the observance of this ritual would have naturally attracted them as well.

According to the Gṛhyasūtras, the Puṁsavana Saṃskāra should generally be performed in the third or fourth month of pregnancy, or if not possible then in the following month. In present practice, however, it is customary to perform this rite at any time from the second to the eighth month of pregnancy. In different communities, the month for performing Puṁsavana is determined according to family tradition. Among the Perikis, it appears from popular custom that the rite is usually performed in the third or fifth month. Since Puṁsavana is a Kṣetra Saṃskāra (a field rite, connected with the womb), it is to be performed only once and not repeated with every conception, as stated by Yājñavalkya.

Various procedures of the Puṁsavana are described, among which the references to the Āśvalāyana Gṛhyasūtra and Kauśika are of special importance. Commonly, in this rite, juice of the banyan tree, or juice of kuśa-kaṇṭaka (a thorny grass), or the extract of soma-latā is instilled into the nostrils of the pregnant woman. Along with this, a water-filled pot (kalaśa) is placed on her lap, and the husband touches her abdomen while reciting the mantra “Suparṇo’si” (“You are the well-winged one”). The purpose of this touch is to ensure the proper growth of the fetus and to prevent miscarriage or deformity.

According to the Āśvalāyana Gṛhyasūtra, curd prepared by churning the milk of a cow whose calf is of the same color as itself is placed on the right palm of the pregnant woman…

She is then asked to drink it. Afterwards, the husband is to recite the mantras “Ā te garbho” and “Agniretah”, and instill juice of dūrvā grass into her right nostril, and then touch her heart. In the Kauśika Sūtra, a slightly different ritual is described: fire is to be produced by the friction of aśvattha (peepal) and śamī wood. Then, ghee from a cow that has a calf is to be offered into that fire. The same ghee is then dropped into the right nostril of the pregnant woman. That fire is also mixed with honey to prepare a drink, which is then given to her. After this, wool (lokaḍa) or jute threads (in the Perika community, jute used in weaving sacks) are spread out, and then tied around her wrist to steady the fetus. A symbolic ritual with bow and arrow is also performed for the stability of the fetus.

Although the Puṁsavana rites appear in different forms, they all seem to share a common thread — medicinal value. There is an underlying belief that sprouts or shoots of a divine plant or creeper would help the woman in bearing a male child. Similarly, a son resembling the mother is said to be fortunate. Thus, curd prepared from the milk of a cow whose calf is of the same color as itself is prescribed. The belief is that the child born will be fortunate and prosperous.

In Maharashtra, this ritual is popularly known as Oṭī Bharṇe. It is more of a social custom. On this occasion, the pregnant woman is adorned from head to toe with flower garlands, and a bow and arrow are placed in her hands. This appears to be a part of fulfilling her cravings (dohāḷe). It is natural for a pregnant woman to wish for a son of her desire, and this ceremony is performed to fulfill that wish.

In this context, the Bhāgavata Purāṇa narrates a noteworthy story: when Diti desired to have a son who would slay Indra, Kaśyapa advised her to observe the Puṁsavana vow (vrata). (Bhasaṅko, Vol. 5580). This clearly shows that the Puṁsavana Saṃskāra was intended to ensure that the child born would be valiant and intelligent.

Sīmantam – Sīmantonnayana:

This too is a prenatal rite (garbha-saṃskāra). The purpose behind it is that by fulfilling the desires of the pregnant woman and keeping her content, the child in the womb grows healthily. In this stage, a woman develops many cravings. These desires are called dohāḷe in Marathi and dohada in Sanskrit. Dohada literally means “the desires of two hearts.”

She has two sets of desires — her own and those of her fetus. In fact, it is believed that the wishes expressed by a pregnant woman regarding food, drink, or other things are not truly her own, but are the desires of the child in her womb, spoken through her. At such a time, it is the duty of her husband, and by extension her in-laws and her parental family, to fulfill whatever wishes she expresses. This practice is called “supplying the cravings” (dohāḷe puraviṇe). (Bhasaṅko, Vol. 3, p.781).

“While celebrating the fulfillment of pregnancy cravings”

While speaking of fulfilling the cravings of a pregnant woman, Ayurveda states:

“Dohadasya pradānena garbhāśa doṣam avāpnuyāt” —

That is, if the pregnant woman’s desires are not fulfilled, the fetus may be harmed.

Hence, it is believed that Sīmantonnayana is important for ensuring the healthy growth of the fetus. By fulfilling the wishes of the pregnant woman, it is as though the desires of the fetus itself are being satisfied; in this way, the ritual becomes a kind of garbha-saṃskāra. For this reason, the ceremony of Dohāḷ Jevan (the special meal for the expectant mother) is performed.

In truth, Dohāḷ Jevan is the very first celebratory function in honor of the pregnant woman. It is usually performed in the seventh month of pregnancy, and the scale of the meal depends on the means of both her in-laws and her parental family.

Among the Perikis, it is customary to seat the pregnant woman on a swing decorated with flowers. On the day of Dohāḷ Jevan, the expectant mother is dressed in a green sari and adorned with green bangles. A floral net is placed on her head, and she is seated inside a decorated canopy (makhara). Her lap (oṭī) is then ceremonially filled. Married women (savaṣṇīs) are invited for haldi-kunku (auspicious turmeric and vermilion ritual). A floral belt is tied around her waist, a crown of flowers is placed on her head, and a bow and arrow made entirely of flowers are placed in her hands. This floral adornment is called vāḍī bharṇe in Marathi.

On this occasion “The women gathered together sing Dohāḷ songs (songs for the expectant mother). For example:”

**“The seventh month has begun, the womb round like a coconut,

In the palace the decorations are arranged.

Fragrant flowers are woven into a garland,

A net is placed upon the head, as the moonlight gently falls.

Women of the town gather together,

Singing sweet and melodious songs.

Some tease and joke in unison,

While offering turmeric, vermilion, betel leaves, and areca nut.”*

(from Bhasaṅko, Vol. 3, pp. 781–82

Jātakarma (Rite at Birth):

This saṃskāra is to be performed immediately upon the birth of the child, even before the cutting of the umbilical cord. Its purpose is to protect the newborn from various evils and misfortunes, and to ensure that the child attains long life, valor, and intelligence.

Indeed, from ancient times, human beings have been performing certain rituals at the birth of a son. For primitive man, the origin of life from life, or of a human from another human, was a great wonder. He therefore attributed this event to some supernatural power — and rightly so from his perspective. At such a moment, the first thought in his mind was: how will the mother, exhausted by childbirth, and the fragile newborn infant be protected? Would the child be harmed by an evil glance? Might unseen spirits or demons cause affliction? Driven by such anxieties, early man began to devise and perform certain rituals in one form or another. At the same time, he also desired purity for both mother and child, and for that reason additional rites and observances were created. Among them, this became established later as a saṃskāra.

Though the rite is practiced in somewhat different forms, its purpose is seen to be the same. The father of the child first looks upon the face of the infant, then bathes, and resolves with a vow (saṅkalpa) that because the newborn has been touched by the waters of the womb…

The purpose of this rite is that the impurities acquired at birth should be removed, and that the child’s intellect and lifespan should increase. With this resolve, the father performs the Jātakarma Saṃskāra. Ghee and honey are mixed together, into which a piece of gold is dipped and stirred, and this mixture is given for the child to lick. Then, bringing his mouth close to both ears of the infant, the father blesses him with the mantra “Śataṃ jīva…” (“May you live a hundred years…”).

Although this is the main procedure, certain variations are observed. In some places, after seeing the face of the newborn son, the father dives into a river or tank fully clothed. As he leaps into the water, the splashing drops are believed to serve as libations (tarpaṇa) to the ancestors, satisfying them. By this act, the father feels freed from his ancestral debt (pitṛṛṇa), with the faith that his son, in turn, will perform śrāddha and tarpaṇa rituals to satisfy the forefathers.

After bathing, the father returns to the lying-in chamber (where the mother and newborn are). At the doorway, he lights a fire pit and throws mustard seeds and husk into it to kindle the flame. He believes that this will ward off evil spirits and protect the infant.

The first act of Jātakarma is the generation of intellect (medhā-janana) — the imparting of intelligence to the child. For this reason, the child is given the ghee–honey mixture to lick. The natural desire is that the newborn son should grow up intelligent.

The second act of Jātakarma is for long life (āyuṣya). For this, the father whispers life-bestowing mantras into the child’s ears. He then offers gratitude to the very earth on which the son was born. Afterwards, wishing that the child may grow strong, valorous, and pure in life, he touches the infant’s shoulders while reciting the mantra:

Āśmā bhava paraśur bhava hiraṇyam astṛtaṃ bhava।

Ātmā vai putranāmāsi sa jīva śaradaḥ śatam॥

(Pāraskara Gṛhya Sūtra 1.16)

That is: “O child, be firm like a stone, be as powerful as an axe, be pure and invincible like gold. In truth, as my son, you are my very soul. May you live a hundred autumns (years).”

Having said this, he praises the mother as well, and the cutting of the umbilical cord is performed. The mother then nurses the baby for the first time. The father places a vessel filled with water near the mother’s pillow, saying: “O divine waters, just as you sustain the universe together with the gods, in the same way protect this mother and child who are in the lying-in chamber.” By invoking, “Take care of the mother in childbirth,” the Jātakarma Saṃskāra is thus brought to completion.

Jātakarma – Additional Ritual Practices:

As soon as the pregnant woman begins to experience labor pains, a midwife is called. She assists in the delivery, cuts the newborn’s umbilical cord, wipes the child clean, places it in a winnowing basket (sup), applies a black dot of soot (tīṭ) to ward off the evil eye, and wipes the floor of the kitchen all the way down to the threshold. Afterwards, the baby is laid to sleep in the mother’s lap. For this purpose, a special cloth (in Telugu called maśīpelka) is used to wrap the baby from head to toe. The intent behind this is clearly to protect the infant from any evil glance.

In some families, the mother is washed with hot water after delivery, and her entire body is smeared with turmeric. On the third or fifth day, she is given a bath, and then with her hand a lamp of ghee or castor oil is lit. A heated needle is then applied by the midwife around the infant’s navel—two marks above, two below, and one each on either side. It was believed that this protected the baby from abdominal swelling and diseases caused by wind (vāta). Similarly, placing an axe or sickle at the door of the birthing chamber was thought to guard the child from evil spirits or sudden infant illnesses (paṭkī). A wooden plank was also placed under the head side of the mother’s bed, again with the intent of protecting the infant from misfortune.

Every morning, the baby was given castor oil to drink, with the belief that it would regulate digestion. On the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th, 13th, 15th, 17th, 19th, and 21st days, the child was bathed together with the mother. This practice is called Purudu Poyuta in Telugu. The Periki community believes that this Purudu rite is completed in 21 days. In rural areas, away from the cities, this practice is still observed, but in urban Periki society, it has fallen into disuse.

On the fifteenth or twenty-first day after childbirth, following her bath, the mother is taken by two married women (saubhāgyavatīs) to the well. From her hands, into the well she Curd is sprinkled over her, after which she is made to draw water from the well. She is then taken around the well in circumambulation and instructed to bow to Goddess Gaṅgā. The purpose behind this is that the new mother should remain ever-auspicious (saubhāgyavatī) and be blessed with happiness and prosperity. Before this, three balls of rice mixed with chili paste are placed on the well, and these are then given to the accompanying married women (saubhāgyavatīs).

After returning from the well, a cradle ceremony is performed by tying a cradle for the infant, and the Dolotsava (swing-festival of the deity) is celebrated. On this occasion, especially among the Perikis, the ritual of worshiping the Gantā (sacred bell) is performed, and songs are sung.

With the passage of time, this Jātakarma Saṃskāra has now almost completely disappeared. In some places of the Coastal Andhra region, faint traces of this rite can still be seen, but in Maharashtra there is no longer even a sign of it.

Nāmakaraṇa (Naming Ceremony):

The rite and celebration of giving a newborn child a name is called Nāmakaraṇa. When human beings gradually abandoned isolation and began becoming social, collecting around themselves objects useful in daily life, the need arose to assign names to those objects. When it became clear that without names even interpersonal dealings were hindered, people also began to give names to one another. Once names were given, social interaction became smoother. With a name, there was no longer a need for elaborate description — the specific person came directly to mind. Calling and addressing others became easy. As soon as the importance of personal names was realized, it became essential to give a name to every child born, whether boy or girl.

Determining the name of a child is seen to be connected with the religious sentiments of the community. Generally, in ancient times, it was prescribed that a child’s name should be linked to the family deity (kuladevatā) or the presiding divinity. While naming a child after the family deity, suffixes such as dāsa (servant), bhakta (devotee), datta (gifted by), or śaraṇa (one who has taken refuge) were often attached to the deity’s name. The worldly or secular name…

The worldly name (laukika-nāma) is kept for purposes of social interaction, and it is this name that holds primary importance. Such a name is usually chosen to suit the family’s culture and prestige, or else to be auspicious, easy to pronounce, and pleasant to hear.

However, there also exists the practice of giving kṛtsita-nāma — names of a derogatory or trivial nature. Kṛtsita means one that denotes worthlessness or insignificance. If the children of certain parents did not survive, then it was customary that a child born thereafter would be given a name of this kind. Names such as Dagdu (stone), Dhondu (rock), Bhiku (beggar), etc., were believed to ensure the survival of the child and to lengthen its lifespan.

The Ritual of Nāmakaraṇa (Naming Ceremony):

First, the host (father) performs ācamana (sipping of sanctified water) and prāṇāyāma (breath control), and then makes the following resolve (saṅkalpa):

“Mamāsya śiśoḥ bīja-garbha-samudbhava-doṣa-nivaraṇāyāyuḥ-abhi-vṛddhi-vyavahāra-siddhi-dvārā Śrī Parameśvara-prītyartha nāmakaraṇaṃ kariṣye.”

The meaning of this is: For the removal of defects arising from conception and birth, for the increase of his lifespan, for success in social dealings, and for the pleasure of the Supreme Lord, I am performing this naming ceremony of my child.

In the Periki community, this rite is observed on either the 12th or the 21st day after birth. The house is cleaned, and all relatives are invited. The mother and the newborn are dressed in new clothes, and gifts are brought for them. Relatives from both the mother’s and father’s side participate.

To protect the child from the evil eye and to enhance his manliness, valor, and heroism, a talisman of tiger’s claw (vāghanakha tā’īt) is tied around his neck. Lentils (either pigeon-pea or chickpea) are boiled with salt, and this preparation is placed on the infant’s stomach while he lies in the cradle. Incense smoke is waved beneath the cradle. Then, each of the relatives, according to their own wish and sense of propriety, suggests a name for the child. But finally, the fixed name is chosen from among the names suggested by the paternal relatives.

On this occasion, neighbors, friends, and extended relatives are also… Guests are invited for the occasion. In earlier times, chickpea or pigeon-pea lentils were distributed as prasāda to them, but nowadays, betel leaves with banana, areca nut, or coconut (tāmbūla dekhe) are given as auspicious tokens. Formerly, children were often named after ancestors, elders, or renowned personalities of the land. Nowadays, however, names of film actors and actresses are given, as well as attractive names borrowed from other communities. In short, naming too has become a matter of fashion and modernity.

Some people consult the midwife (sūin or dāī) when choosing a name. She suggests many names in relation to the newborn and finally selects one, which the family adopts. Even today, some continue to follow this practice, although priority is usually given to ancestral names or divine names.

At times, names are also chosen based on the child’s birth-star (nakṣatra) or the lunar month of birth. While doing so, there exists a custom that a girl’s name should contain an odd number of syllables, whereas a boy’s name should contain an even number.

The parents recite a mantra into the infant’s ear: “Vaido vaiputra nāmāsi sajīva śaradaḥ śatam” — meaning, “May you gain Brahma-knowledge and live for a hundred years.” Both parents then kiss the child on the forehead. In this ritual, along with prayers for the child’s welfare, there is also an expressed hope that he will respect the supreme divine spirit and contribute to the welfare of the world.

Within the first year after childbirth, the mother and infant are sent to the woman’s parental home. Before leaving, a stone is placed under the cradle so that it may not remain empty. At the boundary of the village, three earthen balls are placed together, and a small sapling (Tangadi Cheṭṭu) is planted upon them. The mother and child are then asked to cross over it. The woman stays with her parents for three or five days and then returns to her in-laws’ home. On this occasion, the child’s maternal grandfather or maternal uncle, according to their means, gives clothes, ornaments, or other gifts and sends them back with goodwill.

In recent times, however, the religious ritual of Nāmakaraṇa is rarely observed. Instead, relatives and married women are invited, the mother’s lap (oṭī) is ceremonially filled, the infant is placed in the cradle, and the child is given a name. (Bhasaṅko, Vol. 5, pp. 30–32)

(33) Sometimes the naming of the child is performed on the twelfth day, and therefore it is also called “Bārse.”

Annaprāśana – First Feeding of Solid Food:

The ritual of giving a child its first morsel of food is also a part of the saṃskāras. This rite is to be performed within the first year. If the child is a girl, an odd month is chosen; if a boy, an even month is chosen for the ceremony. Among the Perikis, it is sometimes performed in the 8th, 10th, or 12th month. In the Coastal region it is called “Annam Muṭṭi-chḍam.”

During the Annaprāśana ceremony, the child is dressed in new clothes. The rite is usually performed by the mother herself or by an experienced elder woman. A mixture of curd, ghee, honey, milk, and rice is prepared into a soft consistency. The child is made to wear a ring on its finger, and then fed the first morsel. It is believed that these foods are conducive to longevity and wellbeing.

Afterwards, married women (saubhāgyavatīs) wave lamps (ārati), bless the child, and sing songs. Books, gold, or other objects are then placed in front of the baby. Whichever object the child touches or gazes at intently is believed to indicate his or her future inclination or destiny. This custom is still observed in many parts of Andhra even today.

At the same time, when the upper teeth first appear, the child’s teeth are not directly shown to the maternal uncle. Instead, they are shown as a reflection in a bowl filled with coconut oil.

Cūḍākarman – First Tonsure (Removal of Hair):

Cūḍa means a top-knot (śikhā). The ritual of shaving a child’s head for the first time, leaving only a tuft of hair, is called Cūḍākarman, Cūḍākaraṇa, or Cūḷa. In Maharashtra, it is called Jāvaḷe Kāḍhṇe (tonsure). It is considered auspicious to perform this rite in the first, third, or fifth year after the child’s birth.

The procedure is described as follows: On an auspicious day, after performing saṅkalpa (ritual resolve), Gaṇapati pūjā, Puṇyāhavācana, Gantā pūjan, and invocation of the family deities, a fire ritual is prepared. Then rice flour, black gram, and sesame seeds are each placed separately in small bowls (droṇa). After this…

The mother sits with the child on her lap, facing west of the sacred fire. The father stands to her right side, holding cold water in his right hand and warm water in his left. He pours both waters together at once into a vessel, and with that water he rubs the child’s head three times. Afterwards, the barber is instructed to shave the child’s head. The barber removes all the hair, leaving only a small topknot (śeṇḍī). The shaven hair is placed on cow dung, then buried in the cowshed, or cast into a water body, or concealed near the bank of a pond or river. In this way the saṃskāra is completed. (Bhasaṅko, Vol. 3, p. 436).

In the Periki community, the first tonsure ceremony is usually performed in the seventh or ninth month. Some families, however, perform the hair-cutting (keśavapana or jāvaḷe kāḍhaṇe) after one year or even three years. Commonly, vows (navas) are made to ensure safe childbirth and to protect the child from harm. For this reason, the ceremony is often performed in the premises of a temple. Especially among the Perikis of Telangana and the villages of Yavatmal district, the first tonsure is performed at the temple of Adelli Pochchavva, where the child’s hair is offered to the goddess. In Maharashtra too, the Vāghobā shrine in Bhandara district is famous for this ritual, where tonsuring, vows, and related ceremonies are held.

In some places, the rite is carried out in the local temple, or if that is not possible, in front of the household Tulsi Vrindavana (sacred basil shrine). At the beginning of the ritual, the maternal uncle cuts three or five strands of the child’s hair with scissors, after which the barber completes the shaving of the head. For this occasion, many relatives and friends are invited, and the rite is performed in their presence. Guests present the child with gifts, placing them into the infant’s hands. Afterwards, a communal feast (paṅkti bhoja) is held.

Karṇavedha – Ear Piercing:

Alongside the tonsure, the ritual of piercing the child’s ears is also performed. According to the Baudhāyana Gṛhyasūtra, the child’s ears should be pierced in the seventh or eighth month after birth.

The procedure of Karṇavedha is described as follows: In the forenoon, the father sits facing east, holding the child on his right…

Touching the right and left ear of the child, the father recites the mantra “Bhadaṃ karṇebhiḥ śṛṇuyāma” (“May we hear auspicious sounds with our ears”). Then, a skilled person or a goldsmith pierces both ears of the child. If the child cries during the piercing, honey is applied to its mouth. Nowadays, it is common to pierce the ears on the twelfth day after birth and to place small rings (saṅkule) in them.

The custom of piercing parts of the body to wear ornaments is seen among all civilized, semi-civilized, and uncivilized communities of the world. From this, it is clear that the practice is extremely ancient. Originally, Karṇavedha was performed both to adorn the ear with ornaments and also for its protection. But today, the ritual of Karṇavedha has almost completely disappeared. (Bhasaṅko, Vol. 2, p. 121).

Akṣarārambha Vidhi – Akṣarābhyāsa

While performing the Akṣarārambha

When the child reaches the fifth year, he is to be taught to write letters. In this rite, betel nuts are placed upon grains of rice as offerings to Gaṇapati, Sarasvatī, the chosen deity (iṣṭadevatā), and the family deity (kuladevatā), invoking their presence. A small altar is prepared with sand, into which a branch of the palāśa tree is fixed, and Sarasvatī is invoked upon it. After duly worshiping all the deities, a fire is established, and oblations are offered into it with the sacred name-mantras of the deities.

Then, the teacher instructs the child to write the letters “Oṃ Namaḥ Siddham” (“Obeisance, may there be success”). These initial letters are called Mātṛkā (the sacred syllables). After this, the deities are ceremonially bidden farewell (udvāsana). (Ṛgveda Brāhmaṇa, K.)

In the secular form of the rite, clay was spread on a wooden board covered with cloth, and the child’s finger was guided to trace the letters “Śrī Gaṇeśāya Namaḥ” or “Oṃ Namaḥ Siddham.” Formerly, this ritual was performed on the day of Daśharā (Vijayadaśamī) or on the New Year’s Day (Varṣa-pratipadā). In present times, this practice has disappeared. (Bhā. Saṃ. Ko., Vol. 1, p. 360)

Among the Perikis, the initiation into learning (Akṣarābhyāsa) is performed when a boy or girl reaches the age of five or six. Most people begin this rite on Guḍhī Pāḍvā (Maharashtrian New Year) or Vijayadaśamī by making the child write the letter “Śrī.” From that point onwards, the child is gradually taught the basic letters and the complete alphabet.

Although today slates and pencils are used for this purpose, in earlier times, children were taught to write on a wooden board (pāṭī) with chalk. Even before that, letters were traced in dust or sand using a finger or stick.

Ordinary families usually performed this ritual at home. The child would be bathed in the morning, dressed in clean clothes, fed curd-rice, and seated before the household Tulsi plant. A slate was placed in his hands, and he was made to write “Śrī” or the letter “Ga” (for Gaṇeśa). An elder would pronounce the letters aloud, and the child would repeat them, thus learning both reading and writing simultaneously. In some places, instead of a slate, a thin layer of clay was spread before the Tulsi plant, and the letters were traced upon it with a finger.

Nowadays, for Akṣarābhyāsa in Andhra, children are taken to the temple of Sarasvatī at Basar. There, the ritual is performed either by the hands of a priest or by a respected elder of the family. However, in Maharashtra this practice has nearly vanished. With the rise of nursery schools and convent schools, children now begin attending school as early as two and a half to three years of age.

Rajasvalā – First Menstruation (Ritumatīhood):

The first onset of menstruation is one of the most sensitive and transformative experiences in a woman’s life. It is, in fact, a revolutionary event in her personal journey. At that moment, as she is not yet fully mature as a woman, feelings of shyness, hesitation, fear, and curiosity overwhelm her, making her reluctant or even afraid to speak about it. Thus, she passes through a state of great confusion. Generally, girls attain menstruation around the age of twelve or thirteen. In Telugu, this is called Samarta or Samurta-Marcha, meaning the first attainment of menstruation.

A girl who experiences menstruation is referred to as Rajasvalā. This marks her entry into womanhood, signifying that she has become capable of marital union. In Telugu usage, terms like Samṛtu, Samarta, Tulimudra, or Puṣpāvatī are employed, all pointing to the fact that the girl has become competent (samartha) for motherhood — she has gained the power to conceive. In daily life, such expressions were commonly used. All these terms ultimately conveyed the same idea: that the girl had become capable of becoming a mother.

In earlier times, the practice of child marriage was prevalent. Boys and girls were married at a very young age, without even understanding the meaning of marriage. In such situations, even after the marriage, the girl would remain in her parents’ home. When she attained menstruation, she was ceremonially sent to her husband’s house. Thus, when a girl first menstruated, the news was first conveyed to her in-laws’ family, after which the rituals were performed.

According to the customs of that period, a girl at her first menstruation had to observe social norms, rules, and ritual practices imposed by society. Today, however, such strict codes and rituals have completely disappeared. Nevertheless, knowing about these old traditions can still be informative.

When a girl first menstruated, she was considered impure. No one would touch her or go near her, and she would be kept in seclusion in a separate room. In that room, a mat was laid, covered with a white cloth, on which she was made to sit alone (in earlier times, mats were made of palm or ṭāṭī leaves). The reason was that, being newly menstruating, she was believed to be vulnerable to the influence of evil forces. Such influences, it was thought, could deprive her of the ability to become a mother. To protect her from this inauspicious danger, she was kept in isolation.

When she disclosed her first menstruation to her mother, grandmother, or some elderly woman, her mother or grandmother would arrange for a ritual: if the girl was already married, palm-leaf mats (ṭāṭī-patra) were brought by her husband, her maternal uncle’s son, or the boy who was betrothed to her (or wished to marry her).

A white cloth is spread over the palm-leaf mat, and the girl is seated upon it. Married women (savaṣṇīs) shower consecrated rice (akṣatā) over her and sing songs. For example, one Telugu song is specially quoted here:

"Suvvī suvvī anacū pāḍarammā, sundarāṅgul ellā gūḍi

Navvumāta kāde kommanāthī samartā ayenammā

Tellā cīra kaṭayanammā drowvā dākṣī yerugādaye

Tallī jūci ceppāgāne talāvan̄ci yeḍacenammā

Buvvā tinuta yerugādammā pū bhoni cūḍārāye."

Meaning of the song:

“All women, please sing ‘Suvvī, Suvvī.’ This is no laughing matter — the girl has now grown up. She wears a white sari, an innocent maiden who knows no deceit. When her mother saw and told her, she lowered her head and began to weep. She does not even know how to eat a proper meal.”

The exact date and time of the girl’s first menstruation is carefully noted. If it occurs at an auspicious time and under a favorable constellation, there is no concern. But if it falls under an inauspicious star or time, rites of pacification (śānti) are performed. During her period of seclusion, the girl is given food without salt and spices, or sweet preparations. It was believed that eating spicy food would weaken her reproductive power (her ability to become a mother).

The clothes she wore during her menstruation were discarded by giving them to the washerman (paritāla). On this occasion, it was customary to offer turmeric and vermilion (haldi-kuṅkum), betel leaves, areca nut, and prasāda (usually roasted chickpeas) to the married women who gathered. In later times, the custom evolved into offering tāmbūla (a betel-leaf set with areca nut and fruit).

For four days, the menstruating girl was not touched by anyone. On the fifth day, her mother-in-law (if she was married) would come and dress her in a new sari and blouse (sāḍī-choḷī), and also present some gifts. Not only that, but she would also bear the expenses of the feast held on that day. In addition, other relatives would visit and offer her sweet dishes. The reason for this was that since the girl had to remain seated in one place until the eleventh day, only easily digestible sweets and light foods were given to her.

On the fifth day of menstruation, the girl was given an abhyanga-snāna (ritual oil bath). At this time, her ornaments and jewelry were secretly removed without her knowledge, and therefore this bath was also called “Dongānillu” (theft-bath). On the eleventh day, she bathed again and was given new clothes. On this day, according to the family’s means, relatives and others were invited, and the occasion was celebrated. Betel leaves (tāmbūla) were distributed. Elders, relatives, and neighbors gave her gifts and offered blessings for her future life. Married women (suvāsinīs) would pound sesame and jaggery or coconut and jaggery in a mortar, prepare sweet balls (lāḍūs), and feed them to the girl. This was called “Chimali.” The married women celebrated this rite like a festival.

In present times, especially among the Periki community in Maharashtra, this rite is no longer practiced. With the near-disappearance of the custom of child marriage, this saṃskāra has been completely abandoned. Even so, when a girl first attains menstruation, a small domestic celebration is still held in the household.

Marriage:

Marriage is one of the highest saṃskāras in human culture, a creative institution that lays the foundation of the family system and the first step into the householder’s stage (gṛhasthāśrama). Through marriage, human life attains completeness. Husband and wife, as two wheels of the chariot of worldly life, begin their journey together here. The cornerstone of familial and social awareness and responsibility is planted at this moment.

Both partners now become ready to move forward on the path of duty. With joy, auspiciousness, and the energy of creation, the couple, prepared for action, takes an assured leap into a new direction. Such is the breadth and significance of this saṃskāra.

Among the many rites performed to enrich human life, marriage stands out as one of the most important. It clearly expresses questions such as: What should be done in future life? How should one live? How should family and social awareness be nurtured? What are the responsibilities of husband and wife?

Marriage has been considered a principal saṃskāra not only among Hindus but in all communities and religions across the world.

From the Purāṇas and Śruti texts, too, the importance of the marriage rite has been described.

It is stated in the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (Ṛgveda Brāhmaṇa 5.2.1.10):

"Without entering marriage and producing progeny, a human being does not attain completeness."

The Baudhāyana Sūtra (2.9.7–8) says: "Every person is born bearing three kinds of debts (ṛṇa-traya). Among them is the debt to the ancestors (pitṛ-ṛṇa), which cannot be discharged without producing offspring."

Through marriage, three purposes are fulfilled: the attainment of sons, the practice of dharma, and the enjoyment of conjugal happiness. In truth, marriage is that relationship where the fidelity between man and woman, and the permanence of their bond, is considered paramount. (Bhāratīya Saṃskṛti Kośa, Vol. II, p. 383).

By marrying and entering the stage of householdership (gṛhasthāśrama), the couple attains a recognized social status. In the marriage ceremony, the groom accepts the bride in the presence of her parents, brothers and sisters, relatives, kinsmen, dear friends, and loved ones, all while the eight guardians of the directions (aṣṭa-dikpāla) and sacred fire (agni) bear witness.

The gathered community offers its good wishes, that this sacred and auspicious bond bring happiness and prosperity into their lives.

Through this holy rite, the woman begins her life as a devoted wife (pativratā). The foremost quality of a true wife has always been regarded as pativratā-dharma — unwavering devotion to her husband. While this inherent virtue exists naturally within her, the marriage saṃskāra strengthens and consecrates it further.

The following Sanskrit verse illustrates how a wife should uphold true pati-dharma — how she should support her husband, and indeed what the very essence of pativratā-dharma is:

"In work, she should be like a servant;

in counsel, like a wise minister;

in feeding, like a mother;

in the bedchamber, like a lover;

in beauty, like Lakṣmī;

in patience, like the very embodiment of dharma.

Thus, endowed with these six qualities,

she is the true wife who upholds the honor of the family."*

Meaning:

In duties, she is like a servant; in counsel, like a minister giving wise advice; in serving meals, like a mother; with her husband in the bedchamber, like Rambhā (the celestial beauty); in appearance, like Lakṣmī; and in patience and endurance, like the Earth itself. A woman endowed with these six virtues is truly the wife who upholds the honor of the family.

Service to the husband is regarded as the sacred duty of the wife. A life without a husband is compared to a lamp without oil! Therefore, it was believed that as long as a woman lived, she should live as a saubhāgyavatī (a blessed wife with her husband alive), and even death should come to her while she remained a saubhāgyavatī. Such was the prevailing social belief.

However, today this belief is no longer entirely relevant. The situation has changed considerably. The main reasons for this are: the growing recognition of equality between men and women, the important role women play in sharing family responsibilities, women’s education, the influence of modern ideas, and self-awareness among women.

Even so, the primary purpose of the institution of marriage has not changed much. Marriage remains as important and auspicious today as it was in earlier times. What has changed radically are the rituals and practices surrounding it.

There are many noticeable differences between ancient and modern marriage customs. Yet one thing remains the same: marriage within the same gotra was forbidden then, and is still considered prohibited today. The role of the priest in solemnizing the marriage was highly significant in the past, and it continues to hold great importance today, for it is through the chanting of mantras by the priest that the wedding ceremony is completed.

Manirkam:

The Telugu word “Manirkam” does not have an exact equivalent in Marathi. Its meaning, however, refers to the custom of giving a daughter in marriage to a maternal uncle’s household. This practice also exists in Maharashtra, where it is believed that the first right of marriage to the maternal uncle’s daughter belongs to the nephew.

In ancient times, when marriages were arranged, this custom of Manirkam was prevalent. There were three main types of such marriages:

- A marriage between a sister’s son and a brother’s daughter.

- A marriage between a sister’s son and a brother’s son.

- A marriage between a sister’s daughter and her maternal uncle (the mother’s brother of the girl).

(The third type of marriage, however, is considered prohibited by the Periki community.)

All these three forms of unions were referred to as Manirkam. In this context, the marriage of Śaśirekhā and Abhimanyu is regarded as an ideal example.

This custom appears to have been established from very ancient times. Even today, in the Periki community, the practice of giving a daughter in marriage to her maternal uncle’s household (ātav ghari bhāchī dene) continues to be observed.

Sashta-Goshta Marriage:

In this marriage system, the household from which a bride is brought is also given a daughter in return — essentially an exchange of daughters. Most commonly, the groom’s sister is given in marriage to the bride’s brother. This is called Sashta-Goshta. Although this practice exists within the Periki community, its occurrence is very rare.

In Telugu, this type of marriage is called Kundamārpiḍi Vivāhālu. Such a marriage is essentially a compromise between families. These marriages succeed only when both families maintain mutual understanding and harmony; otherwise, disputes may arise, leading to adverse consequences for both households. Therefore, both families must take appropriate care.

Remarriage:

In ancient times, remarriage was not generally approved. However, in cases of infertility, illness, or serious vices that disrupted marital life, men were permitted to remarry. At the same time, the practice of polygamy was strongly opposed. Even so, there are numerous examples of men marrying more than one wife. Several such cases are also found within the Periki community.

Pāṭalāvaṇe (Mārumanuvulu):

When a woman was remarried, the practice was called Pāṭalāvaṇe. It seems that such a custom existed in society at the time. Because of the practice of child marriage, marriages were often performed at a very young age. If the husband died prematurely, the girl became a widow, or if a woman was abandoned by her husband for various reasons, her life was plunged into darkness.

However, if a woman showed courage and went through with remarriage, her social prestige increased. In fact, there are even examples of one woman being remarried twice through this practice of Pāṭalāvaṇe.

But did this custom exist in the Periki community? To clarify this, the author of this book personally inquired with some respected and knowledgeable members of the Periki community. They emphatically stated: “Though this custom existed in other communities, it did not exist among the Perikis.”

From this, it appears that the practice was indeed absent in the Periki community. Moreover, records show that in 1940, many social reformers and members of the community made efforts to promote widow remarriage.

In this context, some important information was published in June 1940 in Perika Kula Prakāśikā, on pages 17 and 18.

Through the Perki Association, the issue of widows was raised at that time. Not only that, but efforts were also initiated to enable widow remarriage. In the village of Choupparametla, in Gannavaram Taluka of Krishna District, the son of Mr. Kattika Subbayyagaaru of Choragudi, Mr. Venkateswarulu, was remarried to the eldest daughter of Mr. Angata Rachchayyagaaru of the same village.

To make this remarriage possible, the Perki Association and its workers put in tremendous effort and played a crucial role. This remarriage, which took place in June 1940, was the very first widow remarriage within the Perki community.

The groom, the bride, and their parents received abundant praise from the villagers as well as from dignitaries who had come from far and near. From this, it can be said that although the practice did not exist earlier in the community, it had now begun.

The Bride-Seeing Ceremony:

First, the groom’s family begins searching for a suitable bride. For this, they try to gather information through a mediator or other acquaintances. Once a suitable match is identified, a message is sent through the mediator to the girl’s father, informing him that they wish to come and see his daughter.

Accordingly, a day and time are fixed, and the groom’s family visits the girl’s home. Usually, this group includes the groom’s parents and five others (three men and two women). Among these five, some are generally skilled in practical matters.

Then the actual ceremony of showing and seeing the girl takes place. This is what is called the “bride-seeing” (mulgī pāhaṇe) ceremony.

After the bride-seeing ceremony, both families would hold discussions regarding household background, customs and traditions, social standing, and mutual respect. Once both sides were assured of being socially equal and believed that the marital life would be happy, the kanyāśulka (dowry to be given with the bride) was then decided.

During all these proceedings, the bride and groom themselves did not meet or see one another. The elders conducted the ceremony, exchanged tāmbūla (betel leaves, areca nut, and fruit), and finalized the betrothal (vāḍa-niścaya).

In present times, however, these practices have become outdated. Now, the mutual consent of the bride and groom is considered most important, followed by the dowry to be given to the groom. Moreover, today, the responsibility of finding a suitable groom lies more heavily on the girl’s father than on the boy’s side. Despite such changes, the role of the mediator (madhyastha) continues to remain significant.

Once everything is settled, the betrothal (vāḍa-niścaya) ceremony takes place.

In this rite, the groom’s father offers tāmbūla (betel leaves, areca nut, and fruit) to the bride’s father and says: “Please give your daughter to my son.” The bride’s father, in turn, gives tāmbūla into the groom’s father’s hand and replies: “I am giving my daughter to your son.”

This ritual is known by different names in different regions:

- In Rayalaseema: Gattitattā

- In Telangana: Okkākū Sākṣi Tāmbolam (okka = areca nut, āku = betel leaf)

- In Adilabad: Viḍayam Iḍayam (betel leaf offering)

- In the Coastal districts: Paspu-Kumkum Niścitārtham

- In Maharashtra: Sākṣagandha

At the same time, as part of this ceremony, the groom’s family presents the bride with a new sari and blouse, other clothes, ornaments of gold or silver, and/or dowry, while the bride’s family gives the groom a ring and new clothes.

Horoscope – Wedding Invitation – Marriage Card:

After this, the horoscopes (kuṇḍalī) of the bride and groom are carefully examined by the priest, considering the day, the planetary positions, and the astrological factors. The guṇa-mīlana (matching of qualities) is of special importance. If the horoscopes do not match, sometimes the bride or groom is given another name, and on the basis of that, the wedding rituals are decided.

This invitation states that the daughter of a certain person and the son of a certain person were formally betrothed in the presence of specific relatives and witnesses. It also includes the details of the horoscope prepared by the priest, the guṇa-mīlana, and other relevant information. Furthermore, it specifies that on such-and-such day, at such-and-such time, and at such-and-such place, the wedding will be solemnized.

The priest then hands this written invitation to the bride’s father. In Telangana, this wedding invitation is called Lagṇakoṭi.

From this wedding notice prepared by the priest, the bride’s and groom’s families then have proper wedding invitation cards printed and sent to their relatives and acquaintances, earnestly requesting them to attend the marriage ceremony.

In the Coastal Andhra and Rayalaseema regions, some families conduct the vāḍa-niścaya (betrothal ceremony) at the bride’s house, while others conduct it at the groom’s house. However, in Telangana, this ritual is always performed at the bride’s home.

Once the wedding date and auspicious time (tithi) are finalized, preparations begin in both households. They clean and decorate their homes, sometimes even painting them afresh. About five or seven days before the wedding, the groom is formally declared navaradeva (bridegroom) and the bride as navarī (bride).

This ritual involves giving both the bride and groom a ceremonial bath and dressing them in new clothes. A red mixture made from turmeric and lime (parāṇī or maravaḍa) is applied to their feet. Married women (suhāsinīs) place sacred rice grains (akṣata) on them, and these women are given tāmbūla (betel leaves, areca nut, etc.) in return.

Then, rice, pulses, sari and blouse, seven or nine khaṇs (traditional measures of grain), turmeric, vermilion, dates, betel leaves and areca nuts, flowers, fruits, ₹151 in cash, and a gold chain are packed into a chest (pēṭī). This chest is carried by the washerman (parīt) from the groom’s side to the bride’s home.

Along with this, a group of 5, 7, 9, or 11 people — always in odd numbers — also accompany the chest (in earlier times, they traveled to the bride’s home in bullock carts). At the bride’s home, her family warmly welcomed them with honor and respect, making arrangements for their bathing, meals, and lodging. Even the bullocks of the cart were carefully tended to.

After this, in the presence of many respected persons of the village and relatives, the chest (pēṭī) is opened, and all the items placed inside are shown to everyone. The chest is then formally handed over to the bride’s father. Earlier, only men were present during this viewing, but nowadays both men and women participate — in fact, the number of women tends to be greater.

The very same people who brought the chest are the ones who, on the following day, bring the bride with honor in a palanquin, a cart, or a bullock cart (depending on their means) to the wedding pavilion (vivāha-maṇḍapa) at the groom’s house. Along with them, other relatives and family members also accompany the procession.

All these guests are then taken to a designated house (parī — usually belonging to a friend, neighbor, or relative), where they are provided arrangements for a short rest and preparations. This place is referred to as the jānośāche ṭhikāṇ (the halting place of the bridal party).

Jānosa (Viḍidī):

The dictionary gives the meaning of Jānosa as follows: “Jān – ni – vasā – Jānosa: the temporary stay or halt of the bride’s or groom’s party at a particular place; a resting house for the bride’s or groom’s side; the house provided for the bridal party.”

That is, when the wedding guests (varāt or procession) arrive at the wedding location, they do not go directly to the wedding pavilion. Instead, a designated place is arranged for their rest and temporary stay. This is called Jānosa, and in Telugu, it is referred to as Viḍidī.

In Rayalaseema and Coastal Andhra, weddings were generally held at the groom’s house, whereas in Telangana (in some communities), weddings were held at the bride’s house. Thus, whichever side was hosting the wedding was also responsible for arranging the Jānosa for the arriving guests.

Special care was taken for the comfort of guests staying at the Jānosa, especially those who had traveled from distant places. A special drink called Pānakam was served to them to relieve their fatigue. This drink was prepared from jaggery, tamarind, neem blossoms, cumin seeds, and other ingredients — essentially an Ayurvedic preparation. It was traditionally carried in containers hung on a double-ended yoke (kāvadi) by two people and brought to the guests.

Every effort was made to ensure that the guests received complete rest. Later, local people would come to escort them to the wedding venue. They would welcome the arriving parties with rose petals of various colors, exchanging greetings, and then bring them ceremoniously to the wedding site.

Earlier, weddings lasted for five days, with specific rituals performed on each day. The details of these ceremonies will be explained further ahead.

First Day:

In regions where the wedding takes place at the bride’s house, the groom is ceremonially brought to the bride’s home, and his toenails are trimmed. After this, oil is applied to his body, followed by a paste made of turmeric and gram flour, after which he is given a ritual bath.

Five Sūrya-bhaktas (male devotees of the Sun) and two Puṇyāṅganās (auspicious married women) anoint him with sandalwood paste and apply vermilion (kuṅkum). These Sūrya-bhaktas and Puṇyāṅganās must be married; there is no restriction on age. This signifies that the women should be suhāsinīs (whose husbands are alive) and the men should be knowledgeable and experienced in these customs.

On the wedding day, it is necessary for these Sūrya-bhaktas and Puṇyāṅganās to observe a fast. Even today, this ritual is practiced in the Telangana region and in the Guntur and Krishna districts. A special feature of this custom is that for the entire five days, the Sūrya-bhaktas and Puṇyāṅganās do not speak to anyone. To prevent even a single word from slipping out by mistake, some even tie a cloth over their mouths. The exact reason for this silence, however, is not mentioned anywhere. What is clear is that widows and widowers are strictly prohibited from performing this role.

Second Day:

On this day, the clay pots required for the wedding rituals, called Āiraṇi Kuṇḍalu in Telugu, are brought from the potter’s house. The pots are first anointed with turmeric and vermilion, worshipped with ārati, and then brought home amidst singing, music, and great celebration. They are welcomed into the house with great honor and joy.

While bringing these pots (chāvrut), a ceremonial umbrella (ambāri) is used. This umbrella is made by lifting a blanket or sheet on all four sides with a stick in the center, giving it the appearance of a canopy. Under this umbrella walks the person carrying the pots along with the woman holding the ārati.

Among wealthy families, these pots are decorated and even adorned with gold ornaments, solely as a display of their prosperity and status. Āiraṇi here symbolizes Goddess Mahalakshmi, who is considered the presiding deity of all. Worship of Mahalakshmi through these pots is believed to ensure that the married couple’s life will be prosperous and harmonious.

The potter who makes these Āiraṇi pots is given a customary gift (mirasī), which may include food grains, money, or other offerings in appreciation.

On this day, another ritual is performed where a sack, a wooden board (paṭ), and a measuring basket (bāshiṅg) are placed in a temple. From there, the priest carries all this material to the wedding house. For this service, the priest is given one sher of rice, a coconut, a blouse piece, and some money. Similarly, the barber brings the wooden sandals (khaḍāv) and a small knife (kaṭṭi) meant for the groom.

Third Day:

The most important ritual of this day is tying the wedding bracelets (kaṅkaṇa) on the bride and groom. For this, they are first massaged with soapnut oil (prepared by soaking ritha and extracting its juice). Afterwards, their bodies are smeared with oil, gram flour, and sandal paste, and then they are bathed. This bath is called Talanti Snanam in Telugu. By pouring water over their heads, the bride and groom are ritually purified.

After this bath, the bracelets (kaṅkaṇa) are worshipped. These bracelets are made by applying turmeric to white cotton thread, into which a betel leaf is folded and tied in a knot. Nowadays, instead of a betel leaf, three bilva leaves are sometimes tied into the bracelet. After the worship, the bracelet is tied to the groom’s right wrist and the bride’s left wrist. It is believed that the kaṅkaṇa provides protection and safeguards them from misfortunes.

At the end of this ritual, all the guests present are served a meal. In Telugu, this ceremony is called “Kaṅkaṇāla Banṭi.”

Fourth Day:

This day is the wedding day, the day on which the marriage ceremony takes place. On this day, the cooking holds special significance, because the meals are prepared by the Sūryabhaktas (devotees of the Sun) and the Puṇyāṅgaṇas (married women). This meal, offered first as sacred food to the village deity, is called “Śrībāṇavaṇṭa.”

After this, the Nāgavaḷli ritual is performed, in which the ground is dug and seeds of jute or cotton (sarki) are sown. This act symbolizes the agricultural tradition of the Periki community.

Then, curd rice (dahi-bhāt) is eaten as a light meal. Afterwards, several playful and symbolic rituals are carried out between the bride and groom — such as feeding each other betel leaves and playing with a decorated ball.

The purpose of these rituals is to remove the sense of distance and awkwardness between the couple and to help them overcome their shyness with one another.

Fifth Day:

On this day, the bride and groom are taken out in a grand wedding procession through the entire village. With music, bands, and dancing, the procession moves joyfully across the whole village until it reaches the Jānosa place, where the bride is given an emotional farewell. In this way, the five-day-long wedding celebration comes to an end.

All the relatives, kin, and community members who attend the wedding usually stay for all five days at the house where the marriage is held. This puts a tremendous financial and social burden on the hosts. During each ritual of the wedding, auspicious musical instruments are used—drums, cymbals, trumpets, bands, and shehnai—depending on the family’s means. The use of such instruments is considered a matter of prestige, so families always tried to ensure the music matched their social standing.

A noteworthy tradition in these ceremonies was that as long as the Suryabhaktas and Suhāsinīs (married women) prepared the meals, the barber continuously played the wedding pipe without pause. This shows the extent of dedication people once gave to such functions, being present and engaged full-time for five days straight. Today, however, such a thing has become almost impossible.

In earlier times, the wedding rituals lasted five full days, with extended families and friends staying together at the host’s house throughout. If told today, younger generations might find it hard to even believe.

In the present-day context, the five-day wedding has now been compressed into a single day. Even in this one-day wedding, however, multiple rituals are still observed, making the event just as colorful and engaging.

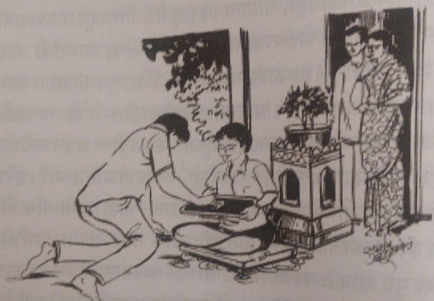

Ritual of Cutting Toenails:

In a one-day Periki wedding, the very first ritual is the cutting of the groom’s toenails. For this ceremony, a decorated space is prepared in the wedding pavilion by spreading rangoli over a cleaned floor. In the Coastal region, paddy grains are spread, while in the Telangana and Rayalaseema regions, either paddy or jowar—measured as ten or twenty sher—is spread, and on top of it a wooden plank (pāt) is placed. This is called the “wedding plank”, because it is on this very plank that the couple later stands to receive the ceremonial showering of sacred rice (akshata) during the wedding rituals.

This method is followed in the Coastal and Rayalaseema regions, whereas in Telangana the practice is to place the “ox yoke” (ōta che jū) instead.

Recently, wooden planks made from the Saalei tree are being used. Then, placing an old cloth on the plank, the bride and groom are seated upon it. Beside them, two baskets containing nine varieties of grains mixed together are kept, and in them, two pestles are placed. After this, some money is waved in ritual offering (ovāḷūn) and placed into a nearby bowl, which is later taken by the barber. Others too offer money, which is handed over to the barber.

Following this, married women (earlier known as Punyangana) take a bowl of milk, dip an arrow into it, and touch the groom’s and bride’s feet, toes, arms, and head with it, while blessing them to gain strength, be free from misfortune, and become capable of self-protection.

Nowadays, however, instead of the married women, it is the barber himself who performs this ritual. Using a pestle (kept in the basket of nine grains) instead of an arrow, he dips it in curd and touches the arms of the bride and groom before cutting their toenails.

In Telangana, this ritual is called “Mailya Polu” in Telugu. In the Medak district, however, this ritual of cutting toenails is performed when a girl first menstruates—on the 3rd, 5th, or 11th day itself—as reported to the author by some respected elders.

After the nail-cutting ceremony, the bride and groom, along with the Suryabhakta (sun-worshippers assisting in rituals), take an oil bath (Abhyanga Snan), involving a massage with oil, application of turmeric-besan paste, and fragrant cleansing agents similar to ubtan. During this bath, traditional songs are sung melodiously.

The Ritual of Cutting Toenails

Marriage:

In very ancient times, Periki marriages used to be performed under a tree. Later, the practice of erecting a wedding canopy (maṇḍapa) in front of the house became customary. Generally, this canopy was covered with palm leaves. If palm leaves were unavailable, branches and leaves of the jambhul (black plum) or umber (fig) trees were used. In more recent times, leaves of any tree are used for covering the maṇḍapa.

Within the canopy, at a suitable place, a raised platform (stage) is prepared for the marriage. This is called the vivāha-vedikā (wedding altar). It is decorated by sprinkling sacred designs (sada-saravaṇ) and drawing rangolis (auspicious patterns). On this platform, the wedding plank (pāṭa) is placed—nowadays generally made from the wood of the sālai tree. However, in ancient times, a tārā was placed instead. (Tārā refers to the wooden pieces fitted on either side of a horse before placing the saddle).

The marriage ceremony itself is conducted by the priest, in accordance with scriptural injunctions, with the chanting of sacred mantras.

In ancient times, during marriage ceremonies, the bride and groom would wear garments dyed in a blood-tinged red color. At present, however, they wear white clothing.

The groom wears a dhoti seven cubits (hands) in length, a shoulder cloth (dupattā) six cubits long, and a turban (pāgoṭā or pheṭā) also seven cubits in length. The groom is seated on the wedding plank (pāṭa), and rice grains (akṣatā) are applied to him as a blessing. After this, a sword is tied around his waist, and along with it, a length of cloth about a cubit long is fastened to the sword.

Traditionally, a quiver of arrows would also be strapped to the groom’s back by the sūryabhaktas (ritual assistants). Nowadays, however, only a knife is placed in the groom’s hand. Along with this, a new piece of cloth (a blouse piece) is given, which is later presented to the woman performing the āratī or to the groom’s sister. This practice is still observed in the Coastal region.

In the Telangana region, instead of a knife, an aḍakitti (a small sharp instrument) is used. In the Rayalaseema region, a knife with a lemon fixed to it is placed in the groom’s hand, and he also wears khaḍāu (wooden sandals) on his feet.

The custom of tying the bāśiṅg during weddings appears to have been practiced in almost all castes and regions, both in the past and at present.

Bāśiṅg is an ornament tied on the forehead of the bride and groom at the time of marriage. It is usually made of golden-colored decorative paper, with thin strips of the same paper cut and attached as tassels. Some people also make bāśiṅg from flowers and pearls. To fasten it on the forehead, strings or similar attachments are tied on either side.

Because of this ornament, most of the bride’s and groom’s faces remain covered. Perhaps the practice originated so that they could be distinguished in the crowd or so that they would be protected from the evil eye.

The honor of tying the bāśiṅg on the groom usually belongs to his sister. Two bāśiṅgs are tied on the groom, and one of them is later untied and sent to the bride’s side.

The bride wears a fourteen-hand-long white paṭaḷ (nine-yard sari) along with a blouse. The border of this white sari is dipped in dye and edged with the color prepared for pārāṇī (marwaḍ design).

The bride and groom are adorned with a vermilion kalyāṇ tilak on the forehead and a small dot of kohl on the cheek. Their feet are also decorated with marwaḍ. A mixture of turmeric and lime creates a distinct color, which is used to draw lines and dots on their feet — this decoration is called pārāṇī (marwaḍ).

Songs are sung to accompany each moment of the wedding. These songs invoke deities like Sitaram, Gopikrishna, and Mallanna, and draw parallels by associating the bride and groom with them. They reflect the lifestyle and culture of the Periki people. Depending on the occasion, the songs embody sweetness, meaningfulness, entertainment, and poetic beauty. Moreover, they also express elements of womanhood, social duty, circumstances, traditions, and cultural practices. Filled with literary qualities, these songs captivate the listeners completely.

Worship by the Groom (Varapūjā):

In Periki weddings, certain rituals of worship are performed by the groom, conducted under the guidance of the priest. These include Gaurī Pūjā, Kalaśa Pūjā, worship of the family deity (Kuladaivata Pūjā), worship of the chosen deity (Iṣṭa Devatā Pūjā), and Gantā Pūjā.

The purpose of these rituals is to ensure prosperity and well-being in the married life of the bride and groom. Gaurī Pūjā is performed so that the couple may be blessed with happiness and prosperity in their household life. Gantā Pūjā is unique to the Periki community and is not practiced in other societies. However, in recent times, even among the Periki, this ritual is rarely observed during weddings.

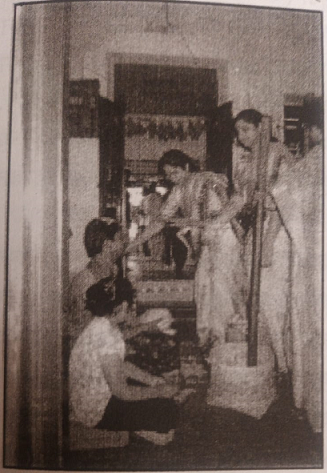

Gantā Pūjā (Bell Ritual):

Beside the wedding altar, a mat made of hemp (boru) is spread, and on it a sack (ganta) is laid out. Pictures of the Sun, the Moon, and Lord Malhār are drawn upon it and decorated with sandalwood paste, rice grains, turmeric, and vermilion. Over this are placed 101 betel leaves, 101 areca nuts, 101 dried dates, and 101 almonds, arranged in an attractive pattern.

After this, in all four corners, two brass pots (loṭe) are stacked one over the other. The altar is then enclosed with a double wheel-like structure (cakkra) tied with threads. Cotton threads are tied crisscross—vertically, horizontally, and diagonally—between the pots, and these threads are fastened to the upper circular structure of the altar. This structure is called sūre (or varaṇī). The sūre is then decorated with chilies, flowers, betel leaves, grains, cotton, turmeric roots, and carrots.

Next to this ganta, a new sack is placed and sprinkled with turmeric. In its center, symbols like the wheel (cakra), trident (triśūla), and crescent moon are drawn with ritual markings. To preserve these images from being erased, more turmeric powder is sprinkled over them. This new ganta is placed within the earlier sūre, and two large pots are placed on it, smeared with turmeric. Between these two pots, an image of Lord Malhār is drawn with sandal paste. The trident, wheel, and crescent are again drawn and covered with turmeric powder. These pots are then anointed with sandal paste and rice grains, and their lids are placed upside down to close them.

In front of the sūre (varaṇī), a cloth is spread and on it four and a half śer (traditional measure) of rice is heaped. A border is drawn around this heap with a finger, and within the boundary an image of Goddess Gaurī is shaped from moistened turmeric and placed there. Offerings (naivedya) such as jaggery, bananas, betel leaves, and areca nuts are placed before her.

After this, the Sūryabhaktas and the bride and groom offer incense and worship the sūre, circumambulating it. Then the bride and groom are led inside the sūre to perform worship and are made to circumambulate it three times.

Gantā Pūjā (Bell Ritual):

Beside the wedding altar, a mat made of hemp (boru) is spread, and on it a sack (ganta) is laid out. Pictures of the Sun, the Moon, and Lord Malhār are drawn upon it and decorated with sandalwood paste, rice grains, turmeric, and vermilion. Over this are placed 101 betel leaves, 101 areca nuts, 101 dried dates, and 101 almonds, arranged in an attractive pattern.

After this, in all four corners, two brass pots (loṭe) are stacked one over the other. The altar is then enclosed with a double wheel-like structure (cakkra) tied with threads. Cotton threads are tied crisscross—vertically, horizontally, and diagonally—between the pots, and these threads are fastened to the upper circular structure of the altar. This structure is called sūre (or varaṇī). The sūre is then decorated with chilies, flowers, betel leaves, grains, cotton, turmeric roots, and carrots.

Next to this ganta, a new sack is placed and sprinkled with turmeric. In its center, symbols like the wheel (cakra), trident (triśūla), and crescent moon are drawn with ritual markings. To preserve these images from being erased, more turmeric powder is sprinkled over them. This new ganta is placed within the earlier sūre, and two large pots are placed on it, smeared with turmeric. Between these two pots, an image of Lord Malhār is drawn with sandal paste. The trident, wheel, and crescent are again drawn and covered with turmeric powder. These pots are then anointed with sandal paste and rice grains, and their lids are placed upside down to close them.

In front of the sūre (varaṇī), a cloth is spread and on it four and a half śer (traditional measure) of rice is heaped. A border is drawn around this heap with a finger, and within the boundary an image of Goddess Gaurī is shaped from moistened turmeric and placed there. Offerings (naivedya) such as jaggery, bananas, betel leaves, and areca nuts are placed before her.

After this, the Sūryabhaktas and the bride and groom offer incense and worship the sūre, circumambulating it. Then the bride and groom are led inside the sūre to perform worship and are made to circumambulate it three times.

Śrībāṇa (Naivedya):

The word Śrībāṇa is derived from the Sanskrit word Bhojana, meaning “meal.” In Prakrit, Bhojana gradually transformed into Boyana or Bhona. In Telugu literature, this evolved into Bonamu, and in common usage into Bonam or Bonālu. Bonālu refers to the ritual offering of food to the village deity.

In the Perika community, during weddings, the term Śrībāṇa carries this very meaning. The Sanskrit word Śrī Bhojana appears in Prakrit in its derivative form, and its intended meaning is “delicious and satisfying food.” In Telugu, bāṇa also means “earthen pot.” Thus, food prepared in such a pot is not only tasty but also sacred. From a health perspective, food cooked in earthen pots is both flavorful and nourishing to the body.

In Indian culture, food is revered as Parabrahma (the Supreme Spirit). Human life and vitality are sustained by food; hence, in weddings, food naturally occupies a place of great importance. The vessel (earthen pot) in which the food is cooked is first worshipped, and the divine essence of the food prepared in it is first offered to Śrī in the form of naivedya (sacred offering).

Therefore, this sacred meal is called Śrībāṇa.

“In Perka weddings, Surya Bhakt (Sun worshippers) and Punyagana, who are regarded as symbols of auspiciousness, themselves prepare this meal, which highlights its significance. Along with honoring the village deity, the purpose of this feast is to provide a sense of satisfaction and prosperity to all attendees.”

Surya Bhakt (Sun Worshippers):

On the wedding day, five Surya Bhakts and two Punyaganas go to the village well with great pomp and music to fetch water. On this day, they observe a fast. After bringing the water, a ritual of grinding turmeric (halad dalane) is performed in the wedding pavilion (mandap). While grinding turmeric, devotional songs are sung. These songs are addressed to the family deity or other deities, with the purpose of ensuring that the wedding ceremonies proceed smoothly without obstacles. During this ritual, turmeric is sprinkled over those present in the mandap, and the qualities of Malanna are praised. In Adilabad district, such songs are sung with great enthusiasm.