Perki, Pairka, Perika is a caste found in South India. How did this caste come to be known by the name Perki? What does its ancient history say? What were its relations with other castes and sub-castes in society, and what is its exact position? What was their occupation, their livelihood, their antiquity, etc.? — all these aspects are discussed in this chapter.

The main focus is on the origin of the word Perki, its different meanings in different contexts, its references in literature, administrative records, scientific treatises, and various dictionaries, and from that the semantic range of the word Perki. While doing so, due to similarities in many reports, there is sometimes repetition, but this cannot be avoided. Because in order to verify the truth, presenting the information from many reports exactly as it is proves useful to the readers, helping them to draw their own conclusions.

According to the Madras Census Report of 1891: “Perki consider themselves an independent caste, but in reality they are a reformed sub-division of the Balijas, and closely resemble the Uppus (Salt) Balijas. Their traditional occupation is carrying salt, grain, etc., in sacks on bullocks and donkeys. Perki are found as sub-divisions of both the Kavarai (Kavarai) and the Balija castes. Some among them have accumulated considerable wealth, and now claim themselves to be Kshatriyas. They say that they fled due to the persecution of Parashurama; some say that they are retired Kshatriyas…”

Now they have come to dwell in the mountains and are known as Perki Puragiri Kshatriyas and Giriraju.

According to the Visakhapatnam booklet:“Periki Balijas are those who live by trade and agriculture, and some among them in the districts of Madras and Visakhapatnam have risen to high positions.”

According to the Madras Census Report of 1901:“The literal meaning of Perike is gunny bag (sack). In short, the Periki are sack-weavers, a Telugu caste resembling the Janappans of the Tamil districts. The gunny industry, involving the manufacture of sacks from jute thread, is a well-known industry in Indian trade.”

According to R.V. Russell, Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India:

“In fact, Periki is a sub-caste of the great Balija community. Nevertheless, owing to a certain distinct status, they are regarded as a separate group. They derived the name Periki from the gunny sacks used for their grain trade. Because of their trade, constant wandering became their habit. Thus, in the beginning, they were a nomadic class and, like the Banjaras and Bhamtas, manufactured gunny sacks and bags. At present, however, many of them have taken to agriculture.”

According to the Indian Census Report of 1921:“Perika is a caste found in Telangana, engaged in carrying salt and grain, trading in cattle, weaving gunny sacks, and other forms of commerce. Periki means sack or gunny bag. The Periki people worship nearly all Hindu gods, but their chief deities are Mallanna and Veeramalla. Gunny sacks are held in special reverence. The original occupation of this caste is the making of ropes and sacks. In recent times, however, they are also seen to have turned towards agriculture.”

According to Syed Siraj-ul-Hasan, Castes and Tribes of the Nizam’s Dominions:

“Perika is a Telugu caste of people who weave gunny bags. Their deity is Mallanna. Their original occupation is rope-making...”

“…and the making of gunny sacks. They transport grain and salt. At present, they have also taken to trade and agriculture.”

From the above texts and reports, it is evident that Peraka means gunny sack. Those who weave gunny sacks, transport salt and other grains on bullocks’ backs in such sacks, and trade in them, and who in more recent times have also turned to farming and other occupations, are the people of the Peraka caste.

Earlier, they are said to have been Kshatriyas—known as Puragiri Kshatriyas and Girirajus. Terrified by Parashurama’s terrible vow to annihilate the Kshatriyas, they adopted a mercantile way of life. Their principal deity is Malhari, and their progenitor is said to be Veeraraju (Veeramallu).

Although Peraka is regarded as an independent caste, reports indicate that in reality it is a sub-caste of the great Balija caste. Their livelihood depends on trade and agriculture. Because they constantly travel for trade, they are also called wanderers.

Since the Perki caste is considered a sub-caste of the Balija caste, it would not be irrelevant here to examine the Balija community itself. According to the Bharatiya Sanskriti Kosha:

“Balija is a mercantile caste of South India. Originally, these were Telugu traders from Andhra Pradesh who, for trade purposes, spread throughout South India. The community has two main divisions: Desha (country or court) and Petha (town). The Desha Balijas trace their ancestry to the Nayaka (Balija) kings of Madura, Tanjore, and Vijayanagar, or to the governors of those provinces. The Petha Balijas are further subdivided into groups such as Gajula and Perike. In Tamil-speaking areas, the Balijas are called Bahugan and Kavarai. Although the Balijas claim themselves to be Kshatriyas, others regard them as a branch of the Kamma or Kapu communities.”

This essentially means that Balija too is not an entirely independent caste but a branch of other communities.

In this regard, a significant reference is found on page 137 of the book The Contribution of the Telugu Community to the Growth of Bombay by Manohar Kadam.

Also, in the February–March 1919 issue of the magazine Telugu Samachar, an important research article titled A Brief History of the Kapu Caste was published.

It states: “In the Census Report of 1901, the following castes were said to fall under the heading of ‘Kapu’:

Lekmari Kapu Elanti Reddy

Padakanti Kapu Motati Reddy

Reddy Kapu Gudati Reddy

Gone Kapu Ling Balija

Varela Kapu Perika

Chittap Kapu Banjivaru

Munnuru Kapu Balijavaru

Krishna Kapu Vanjari

Motati Kapu Dompa Kamma

Pakanati Kapu Gampa Kamma

Telugu Kapu Lingayat Vakkaligaru

Gudtti/Gudi Kapu Telugu Kunbi

Kankama Kapu Chembu Telugu

Gentu Kapu Telugu Are

Lekmari Reddy Vakkaligaru

Pakanati Reddy Racha Telugu

Padakanti Reddy Racha Telugu

All the above castes are grouped under the ‘Kapu’ category.

Among these, the principal castes are Kapu and Reddy. This shows that the Kapu caste is the primary one, and from it, the other castes have gradually branched out. It is particularly noteworthy that in Telangana, most of these castes and sub-castes engaged in agriculture were also serving as soldiers in the military. Among them, some castes are even found to have held positions in state administration.

The Bharatiya Sanskriti Kosha also records that the Kapu caste is referred to as Reddy (Vol. p. 243). Similarly, it is mentioned that Balija is a branch of Kamma-Kapu (Vol. p. 70).

This means that Kapu, Reddy, Kamma, and Balija are kindred castes, closely related to each other. Observing their customs and practices also confirms this, as their cultural…

The customs and traditions are also quite similar. Notably, all the above-mentioned communities claim to be Kshatriyas.Kapus means watchmen or protectors, Reddys means rulers, and Balijas means traders—a kind of triveni-sangam (threefold confluence) that seems to have asserted their rights at that time. Over time, those who progressed became prosperous and assumed the main caste names, while those who lagged behind adopted subcaste names. In this way, many subcastes emerged, though their root remained the same.

After this analysis, it is reasonable to also consider some Balija subcastes closely related to the Periki community. Among these, the Janappan subcaste, mentioned in the Madras Census Report of 1901 and the Bharatiya Sanskriti Kosh, is very closely related to Perikis. Janappan comes from Janapa (hemp). Their ancestral progenitor gave them hemp seeds. From this hemp, they made jute fiber, wove gunny bags, used them for trade, and also used bulls for transport (as described in the Balleshu Mallanna text). They too produced hemp, made gunny bags, and traded with them. This suggests that though today they are treated as two Balija sub-branches, originally they must have been one community. However, since Janappans remained in present-day Tamil Nadu and Perikis spread into present-day Andhra–Maharashtra, the gap between them widened.

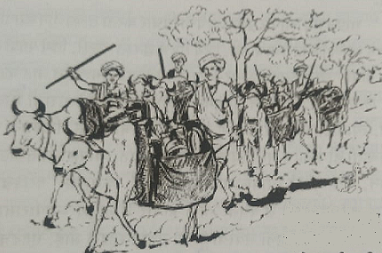

Similarly, even outside the Balija grouping, there are castes closely associated with the Periki community’s traditional occupation and transport system. These are communities such as Banjari, Vanjari, Banjara, Brinjari, Laman, Lamani, Labhan, Lambadi, Lambada, Lambanolllu, Suklir, etc. These groups were engaged in the salt trade, and like the Perikis, they too transported goods on the backs of bullocks. “Loading grain, salt, and other commodities onto bullocks and distributing them almost all over India was their traditional occupation. At times, their caravans had as many as one lakh bullocks,” according to the Bharatiya Sanskriti Kosh (Vol. 6, p. 22).

Thus, the trade in salt or other grains, and the transport of these commodities on the backs of bullocks…

Carrying goods in this manner highlights the similarities between these two groups and the Perikis.

Likewise, Balija means trader, and Banj or Vanj also means trader. In fact, the words Balija and Banj/Vanj are derived from the Sanskrit word Vānijya (trade). This suggests that at some point in the past, these two communities must have lived together.

However, later during British rule, with the introduction of new means of transport such as railways and roads, their traditional occupation nearly collapsed. As a result, they turned towards agriculture, animal husbandry, and manual labor for their livelihood. The same situation also occurred in the case of the Perikis—and this is equally true.

“Perika traders, carrying loads in gunny bags on the backs of bullocks, set out for trade.”

It appears that within the Perika community, several sub-castes gradually emerged. Among them, those who directly wove gunny bags came to be called Pisu (Pichu) Perika; those who traded using gunny bags were known as Perika Balija; and those who later prospered through trade began to style themselves as Racha (Rasa) Perika. A noteworthy example of this is cited in the case of the Gode Murari lineage.

From the available government reports spanning 1891 to 1931, it is evident that the Perikas who used gunny bags for trade were essentially itinerant traders—constant wandering for commerce being one of the chief characteristics of trade during that period.

That means it was barter trade. Goods were exchanged in the form of grain and other commodities. Ordinary people would obtain the items they needed in exchange for their harvested grain. From this practice gradually arose the need to transport goods in large quantities from one place to another according to demand.

Thus, in this barter-based trade system, merchants would carry their goods in gunny bags (Perikalalo), loading them on the backs of bullocks, horses, or donkeys. The gunny bag in which such grain or goods were transported on bullock-back came to be known as Perika, and traders engaged in this method of trade were called Perika Shetlu (Perika Setts or Perika Merchants).

Considering today’s advanced commercial practices, trade in those times was extremely difficult and arduous. Where there were hardly any dirt roads, the question of proper roads did not even arise. Merchants had to make their way through hills, valleys, and dense forests. In these remote regions, the fear of bandits and robbers was very real. At that time, the system of state protection was inadequate, if not entirely absent.

Therefore, for their own safety, merchants would travel in groups and bands. In fact, to protect themselves from robbers, they carried weapons such as spears and swords while going on trading expeditions. The book Vijnana Sarvaswalu notes:

“Merchants would often set out for trade in groups of about a hundred men, carrying both goods and weapons for protection.”

It is further recorded in the Sangraha Andhra Vijnana Kosha that the scholar Perista wrote:

“Merchants who set out from Andhra Pradesh for trading expeditions to Berar in North India would sometimes load their goods on as many as one thousand bullocks.”

Cutting through dense forests, crossing remote hills and valleys, seeking out obscure paths, these merchants faced torrential rains, drought, storms, wild beasts, and the ever-present danger of bandits. Yet, overcoming all these adverse circumstances, they traveled from village to village, trading their goods.

And these merchants were known as the Perikavaru (the Perika traders).

They endured extremely difficult struggles and, by steadying themselves, carved out their own path. In fact, through this life of struggle in trade, they established themselves firmly and strongly. That is why later they became famous as "Perika Shettlu" and began to be respectfully referred to as "Perikavaru".

Over time, the groups of people whose main livelihood came from transporting goods for trade in gunny bags (perika) became popularly identified with the title "Perika." In other words, since their main occupation was transporting goods in gunny bags and conducting trade, they came to be called Perika. Not only that, but later they became recognized specifically as belonging to the Perika caste. From this, it is reasonable to conclude that those who engaged in trade using gunny bags earned the title Perika.

In more recent times, though members of the Perika community have left their traditional professions and advanced into agriculture and other industries, their name in common usage—Perika—has not changed. Interestingly, some other castes, such as the Labhan and others, also used gunny bags for trade. However, they did not acquire the name "Perika," which is noteworthy! Only the people of the Perika community firmly inherited and established this name, and it eventually became their caste identity.

Thus, those who traded through gunny bags (Perikallo) came to be referred to as belonging to the Perika caste. This has also been mentioned in the text Vijnana Sarvaswalu.

Over time, the word Perika stabilized but later appeared in various evolved forms such as Perika, Peruka, Perike, Perka, Perrika, Perriki, Perki, Perik, Perrka, Perikatamu, Perrikatam, Pichu Perika, Perika Setti, Perrika Setti, Perika Balija, Perikarajulu, Racha Perika, Perika Edlu, Perika Bandlu, and many other variations.

From the above explanation, the word "Perika" has consistently meant "gunny bag." However, it is also found to have been used in many other contexts and with different meanings in various places. With this perspective, the term appears in literature, scientific works, and governmental records (such as inscriptions and copperplate grants).

In various dictionaries, Sanskrit lexicons, folk songs, and encyclopedias, the word “Perika” has appeared in different forms. A review of how this term has emerged is taken up further.